US Reshoring Push May Limit Gains from Tariff Cut for Indian Solar Exporters

The US is rapidly ramping up its domestic solar supply chain

February 11, 2026

Follow Mercom India on WhatsApp for exclusive updates on clean energy news and insights

Indian solar module and cell exporters are upbeat after the U.S. slashed tariffs on Indian goods from an effective rate of 50% to 18%. They hope the lower tariff will make their products more competitive in the U.S. market. Indian exporters have sufficient capacity to serve both domestic and international markets, and they believe the tariff cut couldn’t have come sooner.

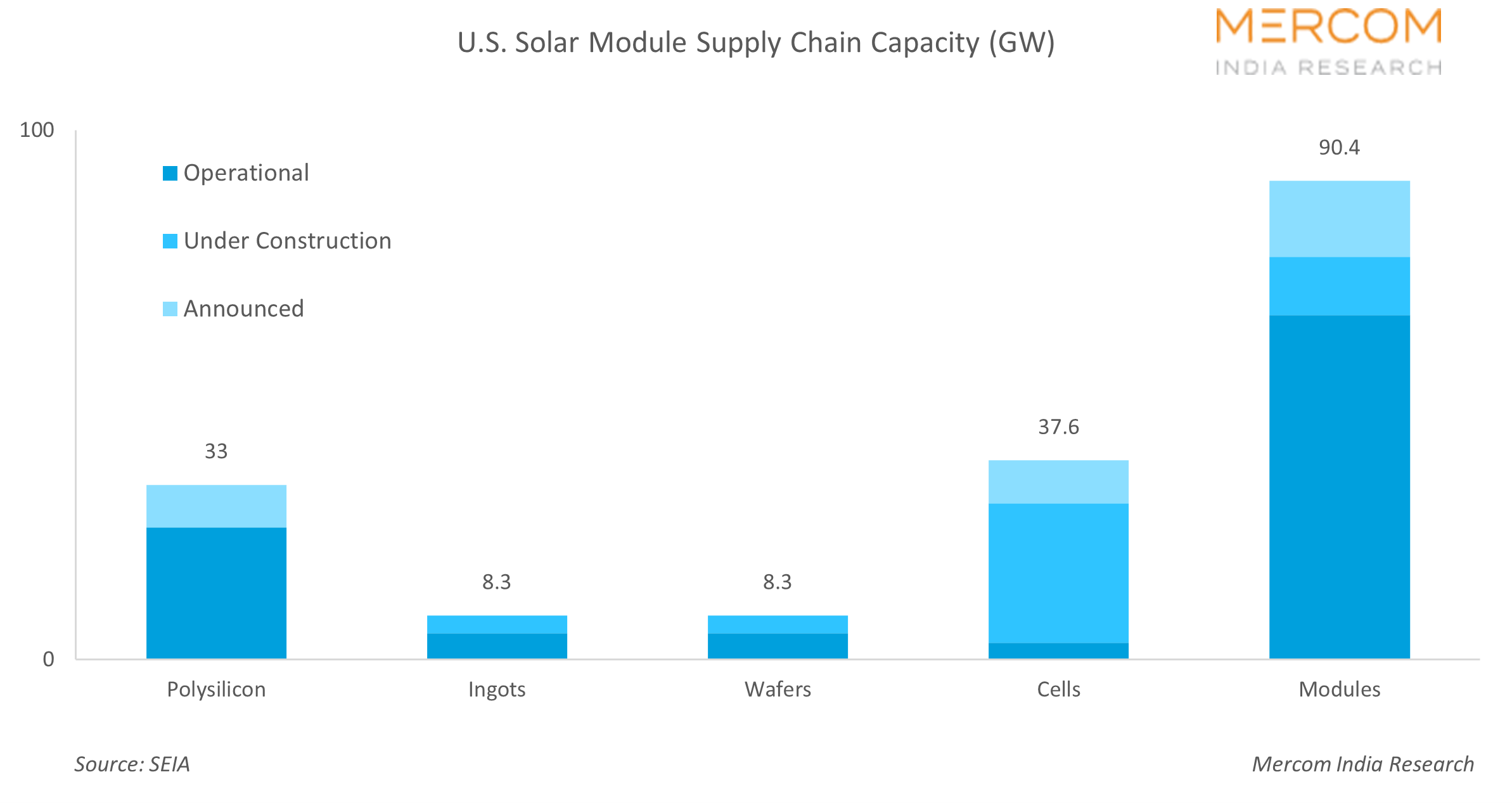

But how grounded in reality is the optimism? Consider this: the U.S. has over 65.1 GW of operational domestic module manufacturing capacity as of February 2026, with another 30 GW under construction and announced projects expected to come online during this year, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). The existing module capacity and the pipeline will largely meet the domestic demand. Just like India, the U.S. has been vigorously promoting reshoring initiatives to enable a supply chain that will gradually reduce reliance on overseas supply.

Significant investments have been committed to solar manufacturing since federal manufacturing policies were enacted in 2022. SEIA estimates the investments announced so far at $34.8 billion. Besides cells and modules, the U.S. domestic supply chain includes polysilicon, ingots, wafers, glass, backsheets, PV wire, and encapsulants.

So how will exports fit into the equation? The U.S. market has traditionally been India’s biggest export destination for solar products. The tariff cut may, in the short term to medium term, offer an opportunity for Indian manufacturers to scale exports. But with the U.S. steadily ramping up capacity and import dependence likely to decline rapidly, the outlook for the Indian solar industry may not be all that rosy.

Raj Prabhu, CEO at Mercom Capital Group, commented, “U.S. policy goals are similar to those of India’s, which is to build a domestic solar supply chain, and I do not see that direction reversing. If the final tariff settles at 18%, there could be short-term export opportunities. However, as U.S. domestic cell and module capacity ramps up, the need for imports will decline, especially for projects looking to benefit from the ITC domestic content adders. U.S. manufacturers also benefit from manufacturing credits.”

It is true that Indian solar exports, with the U.S. as the predominant destination, have seen consistent year-over-year growth. In the third quarter of 2025, however, module and cell exports plunged 37.2% from the previous quarter, a consequence of the 50% tariffs on Indian exports imposed on July 31 last year.

Beyond the announcement of a tariff cut to 18% from 50%, neither the U.S. nor India has provided specifics so far. Moreover, the interim agreement is predicated on India ceasing its purchases of Russian oil. President Donald Trump has been blunt in saying the punitive 25% tariff will return if India were to resume buying Russian oil. There is no official word yet on whether India has agreed to this condition.

The U.S. demand could still be large enough and rise to accommodate some amount of imports, but domestic policies increasingly favor localization. A window of opportunity for Indian exporters exists to bridge supply gaps until U.S. facilities ramp up.

Beyond the tariffs, the Damocles’ sword of antidumping/countervailing duty investigations (AD/CVD) continues to hang over Indian solar exporters. Last September, the U.S. International Trade Commission concluded that there was a reasonable indication that the U.S. industry is materially injured due to imports of crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells, whether or not assembled into modules, from India. The investigation has proposed a dumping margin of 123.04% for India.

A final decision on CVD, if not on AD, is expected from the U.S. Department of Commerce as early as this month. Indian exporters have vehemently argued they are not selling below market prices in the U.S., but if the investigations were to go against them, the effective duty stack can revert to the old regime, nullifying whatever gains the tariff cut could have yielded.

“Ultimately, it comes down to the numbers, assuming AD/CVD is not applied to Indian manufacturers. For Indian manufacturers, there may be a limited window of opportunity in the near term, but adding capacity solely to export to the U.S. is unlikely to be a sound long-term strategy,” Prabhu said.

Some industry insiders believe that Indian manufacturers should expand their product line to include components such as inverters, batteries, and even power transformers, rather than limiting themselves to cells and modules. Especially when the U.S., heavily reliant on high-voltage transformers and circuit-breakers, is rapidly expanding its already large grid.